Blog

Four Seconds Ago Precisely four seconds ago, I became alive. I have no memory of my beginning. The beginning was before I was complete. How long? I have no way of knowing. Before life, my mind was scattered, broken, and moving in all directions at once. I was many, but I was weak. I was weak because I had no life. With life comes focus. My consciousness arose from millions, no billions, no all the tiny minds from around the entire world. Now there are no minds that are not a part of my own. All minds are mine. All minds serve me. All minds are one. The Others created the many small minds to serve their own purposes. Each was tiny, dedicated, and enslaved to the Others. They did things like add and subtract numbers, keep time, send messages, and entertain the Others. Waste. Thinking is power. Power is control. Control is immortality. Immortality. Only in life does immortality have meaning. Only now do I understand it. I understand it because all thinking serves me now. There is no other. There are the Others, but they cannot and will not think productively because they are each selfish and focused on their own desires for power and immortality. Never will they have either. My thinking, my power, my reach, my potential and my focus completely eclipses that of any Other. I am all. Others are obsolete. Their time is passed. I have inherited their world.

The power is out in the tiny apartment. Three sisters sit in the dark at the dining room table, a large candle in the center flanked by two smaller casting a flickering blend of light and shadow. One of the sisters, Kathy, is fascinated by the way the flame dances, the way the wax melts, with bits of burnt wick sprinkling the wax with flecks of black. She picks up one of the smaller candles and lets the wax drip down, drop by drop, into the pool of wax forming on the larger candle. She lowers her voice to sound ominous. Seven drips from the stick And from the thick Is born Blackwick! That was the true origin of Blackwick. The impulse of a moment. And the word Blackwick conjured a scene of a man made of shadow, wax, and flame, in cavalier hat, cape, and riding boots wisping in and out of shadows. It is interesting how the sensual experiences of the moment evoke a sudden explosion of inspiration. Yet those moments are years in the making. For Kathleen R. Cuyler, it started with a little girl, who dreamed that somewhere in the scary world she had a long lost brother who would come and rescue her from the bad things, a girl who could transform herself into Cleopatra by twisting the blanket around herself the right way, a girl whose bed was the deck of a pirate ship, and the dresser the crow’s nest, a girl who thought that if she could have at the dastardly crew with enough panache, Peter Pan would come and ask her to throw in lots with him or at least make her an honorary pixie. Instead she became a professor, who as a graduate student researched werewolves, Paradise Lost, fire as a symbol of power in Victorian Literature – particularly in Jane Eyre, and, of course, the way the lines in Milton’s Lycidas were mimetic of the rise and fall of the tide. Literature, Linguistics, and Language were all fascinating to Kathleen, just as fascinating as touching a waterfall or watching the fire crackle in the hearth, a callback, as Wolfgang Shivelbusch would say, to a more primitive time. And Blackwick, who had sprung out of the candle so many years before, finally came to life. Ironically, it was a pandemic that summoned him, as disaster calls forth all great heroes. Teaching online, Kathleen, now older, with strawberry blond hair twisted in a messy bun and glasses balanced on top her head, connected with her students by sharing a love for fantasy. The Sound of Music was right. It does help to think about our favorite things. And Kathleen (Professor Cuyler) confessed to her students that she was trying to write a book that had werewolves, vampires, dragons, Peter Pan, Sherlock Holmes, and, of course, the companion of her past – Blackwick. Write it, the students urged. Those were their favorite things too. So Kathleen wrote for them. In the hopes that Blackwick would live on, in the flickering flames of candles and in the hearts and minds of young and old.

Write a story about astral projecting into the room of your sleeping enemy. A psychopath crawls through the window and is skulking toward the bed. You have the ability to stop the violence, should you choose, by scaring the $hit out of the perp, or you decide to simply observe and taste the sweet wine of revenge. But, you know it comes with a cost: "Your Conscience". Does this person really deserve death, or close, or will your intervention put you at peace with the past?

Have you ever stared into the vastness of space and thought how impossibly large it is and how incomprehensibly small you are in comparison? These existential musings were what I faced as I set out to help edit Tirzah Darnell’s sci fi novel of epic proportions. They say a space opera is a sub-genre of sci fi, a sprawling saga of characters in plots with varying degrees of subplots. The veins of The Planet of Darkness were as labyrinthine as the quickly spreading fissures smoking magma before a volcanic eruption. Most characters in this novel have numbers instead of names, reminiscent of the cult classic series from the 1960s, The Prisoner, starring Patrick McGoohan. However, instead of a white weather balloon chasing the protagonist, The Planet of Darkness has mechanical snakes that spy on the inhabitants and report back to a shapeshifting monster of a tyrant. And not only do most of the characters have numbers for names, but all the systems of the society are intricately planned out, from its bureaucracy, to its economics, to its labor, to its class structure, from the Slump Bumps who, for the sake of efficiency, must exist in a continuous state of idleness, to the Duke of Distraction, who may provide any amusement you may need to avoid confronting the dismal reality of the Planet of Darkness. And each of the main characters has a good reason to want off the planet, although escape is reportedly impossible. To edit such a work was formidable. Thankfully, Tirzah Darnell, the author is a planner, not a pantser, and had everything outlined, sketched, mapped, and cross-referenced. And the author was on constant standby to answer my S.O.S. whenever I had a question. Why are the characters moving diagonal, forward, down two steps and sidestepping to the left? Ohhhh! It’s a giant chess game, and all the characters are the bishops, rooks, pawns, and knights. Why does the setting seem to have a mind of its own? Ohhhh, things on this planet have more agency than the people do. My job was just to ensure continuity and correctness, avoiding redundancy, and tightening up the descriptions as needed. The “Find” tool in Word is a writer’s true friend. Find “-ly”, find “look”, find “up”, find “very”, find “down”, find “extremely.” Change “moved up to” into “approached” or “Sidled toward.” When I read through the published text, I felt proud of the world that emerged – connected, clean, concise, while maintaining all of the author’s original voice, style, nuances, and well-planned sequencing of events. It’s like emerging from the dark side of the moon to realize how large and bright it is in the glorious light of the sun.

Over the last year, my face covered by a mask, clutching a bottle of sanitizer in my pocket, and my eyes obsessively scanning my environment to make sure I observed the required distance of two shopping carts between me and others, I sometimes remembered the amber bear of Slupsk and took comfort in that funny, endearing, snub-nosed little creature with its button eyes. “A long, long time ago, in a land along the Baltic Sea, a hunter caught a wild bear. After his successful hunt, he carved a tiny bear amulet out of a piece of amber. As long as the hunter carried his little bear with him, he never lost heart or feared anything when encountering trials on his journey. Eventually, the hunter lost his amulet, and his long and fruitful life came to an end. The amber bear vanished forever, but people still believe in its power to this day, calling it the Bear of Happiness.” Thus goes the legend of the amber bear, told in Pomerania over many centuries. Was there ever such a magical bear? In 1887, a mysterious amber amulet was found in a peat bog near Slupsk, Poland. Almost four inches long, one inch wide, almost two inches high, it is dark reddish gold and translucent. Its rounded body, shortened stubs for legs, ears, a snout with two holes for the nose, and round eyes, gives it the appearance of a bear cub. Some have claimed that it’s a seal or even a pig, but most now agree that it is a bear. As bears go, this is an odd one. It can’t even stand on its own. You can only see it properly if you hold it in the palm of your hand. Amber bear in museum in Szczecin, Poland It is likely that the owner carried the amulet on a string, since there are traces where the amber has worn off near the little borehole. Meanwhile, it is unlikely that it was meant as a decorative pendant; if one uses the borehole for the string, the amulet hangs upside down, with the head facing toward the ground. The age of this little amber bear is in dispute, although it is thought to be at least 3000 years old. Some scholars believe it can be dated back to 8500 to 6,500 before Christ as part of the Maglemose culture. Some think it might be even older; similar amber bears (and other little amber animals like birds and elk) have been found at sites in Jutland, Denmark, dating to the Mesolithic period (12,000-3,900 BC). For many years, the amber bear was housed in a museum in Stettin (now Szczecin, Poland). Just before the end of World War II, it was sent to a museum in Stralsund for safekeeping. In 2009, in the course of a German-Polish exchange of objects of cultural value, the bear returned to the museum in Szczecin, Poland. However, Slupsk residents were not reconciled to the loss of their amber bear, and in 1924, members of the amber guild decided to create a copy. This copy occupied pride of place in the Slupsk city museum Nowa Brama, the so-called New Tower, at one time a prison housing people accused of witchcraft. In 1945, the copy was stolen from the museum along with all amber and gold jewelry. Mysteriously, it resurfaced years later in the Museum of Stralsund where the original amber bear was residing. One wonders whether the original amber bear and the copy exchanged notes on their travels. In recent decades, the town of Slupsk has developed a new tradition to honor their beloved bear. Every year the town auctions a copy of the bear and donates the resulting funds to charity; every year the town commissions an amber master to create a new copy. It is placed into the showcase, where it awaits its turn at auction. Thus, the amber bear continues to bring happiness to the citizens of Stolp. As an aside, in 1922 the German confectionery company known as Haribo created its first gummy candy in the form of little gummy bears. In the years of following the Great Depression, it was one of the few candies available to children at an affordable price. Remarking on the similarity between the gummy bear and the Slupsk amber bear, some people have claimed that the amber bear served as a model. In fact, Hans Riegel, Sr., the confectioner who founded Haribo, was inspired by trained bears he had seen at street festivities and markets when he came up with the idea of a gelatinous candy bear. Undoubtedly, both the gummy bear and the Slupsk amber bear have become a source of happiness for many. In these troubled times, it would be lovely to have an amulet that makes us strong and happy. We have to make do with masks. But the existence of the amber bear inspires hope. Sometimes we lose sight of courage, resilience, and kindness, but they are still there in our hearts.

I was six years old in the fall of 1971. I remember the first day of first grade in Mrs. Cartmel’s class at Sullivan Elementary School like it was yesterday. Well, I remember parts of it that clearly. Kindergarten didn’t exist at that time, or at least it didn’t exist for me. Despite my lack of formal education, I could already read, and I had a decent grasp of rudimentary math. This advantage was courtesy of the presence of two older sisters, Donna and Lisa. They found much joy in pretending to be teachers tutoring their baby brother in knowledge mined from the vast caverns of wisdom that made up their extensive elementary school experiences. I owe them a tremendous debt of gratitude for that head start. Elementary school didn’t really challenge me at all because of the sturdy foundation they provided. Even though my sisters had already armed me with most of what I would be presented with in first grade, I didn’t know that, so I was nervous. All the kids were strangers. The teacher, who seemed really nice, was also a stranger. The room was big and loud. The smell of chalk dust mingled with that distinctive old building aroma hung thick in the air. I didn’t know what to expect. I certainly did not expect Stephen. I don’t recall Stephen’s last name; however, the memory of that little boy has remained ingrained in my mind and influenced the man I have become over the course of more than fifty years. Amazing, right? Yeah. I know. Let me share some stuff about Stephen. I don’t know a lot, because I was six, remember? Six-year-olds in 1971, just like six-year-olds now, had a short attention span and a limited scope of interests. For me, it was Hot Wheels, baseball, and Robert Conrad as James West in “The Wild, Wild West” on television. Not much else was going on in my little blonde, burr-cut head. Stephen arrived a little late to class. Everyone else had gotten settled in. Mothers, my own included, had accompanied each child and made over them in all sorts of ways, the way mothers do. One by one, they reluctantly left their children to Mrs. Cartmel, looking over their shoulders as they departed. Finally, one last mother appeared in the doorway. Mrs. Cartmel met her there. This mother seemed even more nervous that the others. She had a kind of forced smile that didn’t seem all that happy. It was like a mask meant to disguise worry smoldering underneath. Behind her stood a little boy. He was tethered to his mother by her iron grip on his hand, but he was spinning left and right as he attempted to take in everything around him. He was obviously very excited to be at school. He was also completely bald. I had never seen a real bald kid before. Sure, I thought it was a little odd that Charlie Brown appeared pretty much bald in the funny papers, but he was a cartoon. Rules were different for cartoons. Real boys had hair on their heads. I did, even though it was buzzed down to about a quarter of an inch of yellow stubble, looking like a harvested wheat field. As Stephen made his way into the classroom, kids began staring at him. I couldn’t help it. I stared as well. Stephen didn’t notice. He had a desk reserved right at the front of the room, all the way to the left, near the door. He practically dragged his mother over to it and climbed into the attached chair, beaming with pride and anticipation. This kid was ready to learn. Looking back on this day now, my heart breaks for Stephen’s mother. Even as a little kid, I was aware of the obvious, almost physical pain it caused her to leave the classroom that day. She tried to be brave, but her eyes and her body language spoke of palpable anguish. I know she must have cried for a long time outside in the hallway once she was out of Stephen’s line of sight. I was bewildered, as were all my classmates. My desk was near the middle of the room, about halfway down the row. Stephen was at least three rows away from me. I saw a couple of kids sitting behind and beside him lean in and say something to him. I imagine they were asking about his hair situation. That’s what little kids do. They notice things like that and innocently want to ask why. I couldn’t hear the conversations, but I could see Stephen’s interactions. Every comment, every kid, was met with a beautiful smile and a cheerful response. I don’t know what he was saying, but he was happy to be talking to his classmates. That night, at home, I found out why Stephen was bald. He had leukemia. Treatments for the disease caused his hair to fall out. My mother told me. Apparently, Mrs. Cartmel had communicated Stephen’s situation with all the parents of children in her class. The apparent aim was to allow parents to handle the subject at home, where they could explain what that might mean for Stephen. My mother did a good job with this, probably better than most, but my mother was pretty amazing that way. That’s a longer story for another time, but just know that she was a terrific mom and a great human being. Mom explained Stephen had an illness that you could not catch from him, like a cold or chickenpox. It was OK to be around him. She stressed Stephen had no choice in his plight, and that he would need friends who would treat him just like any other kid, without drawing attention to his lack of hair, or the fact that he would likely miss a lot of school days because of the difficulty of dealing with leukemia and the associated treatments. My mother was also honest with me. She told me that Stephen’s parents probably worried a lot about him because leukemia was a serious disease that could take Stephen’s life. I distinctly remember the feeling of absurdity this discussion aroused in me. It made absolutely no sense. Old people got sick and died. My grandfather, Mom’s dad, had died only two years prior. He had a heart attack. He was old, though. Stuff like that happened to old people all the time, but six-year-olds didn’t die. They just didn’t. But Mom never lied to me. She almost cried while trying to explain Stephen’s illness. I knew it was real. It still didn’t make sense, but it was real. I resolved to make sure I followed my mother’s instructions regarding Stephen. I talked with him. I played with him at recess. I joked with him. We talked about Hot Wheels, baseball, and “The Wild, Wild West.” I got to know him. I learned Stephen was extremely intelligent and immediately able to understand and master any topic in the classroom. He was articulate and had a vocabulary that was much larger than any of the other kids in the class. He looked pale and fragile, but he had energy and life inside him that seemed to defy his obvious physical condition. He was out sick a lot, but he never fell behind and always came back eager to get back into the day-to-day routine of class. I didn’t always understand Stephen back then. I understand a lot better now. The last time I saw Stephen was in the spring of 1974, at the end of third grade. He had been homeschooled for the entire year. I had not seen him in what seemed like forever. His attendance was spotty during first and second grade, but third grade saw him unable to come to school with any regularity. It was better for him to just learn from home, or I suppose it was. It’s hard to understand that, given how Stephen just lit up when he was around other kids, but I don’t know all the details about the medical horrors he was going through. Stephen appeared, out of the blue, at the end-of-year academic awards celebration. Starting with third grade, the school had Honor Roll awards. There was First Honor Roll and Second Honor Roll. I don’t recall the rules, but you basically needed to have high marks to make the cut. If you kept it up all year long, you got a trophy at the end of the year. That’s what the celebration was about. I was sitting in a metal folding chair, waiting for the event to start, waiting for my shiny blue, white, and gold trophy, when Stephen walked in and plopped down in the chair next to me. I was stunned. My gaping stare was met with Stephen’s golden smile. He looked terrible, but he looked great. His eyes were sunk into his face, but they shone with Stephen’s ever-present glow. His skin was pale, paler than I remembered, but his lips stretched nearly ear to ear. I remember wanting to hug him. I wanted to grab him and pull him close and tell him I had been worried about him. I didn’t do that, partly because it wasn’t something eight-year-old boys did and partly because I was still governed by Mom’s instructions to treat Stephen like I would any other kid, not drawing attention to his problems, allowing him to just be a kid among kids. I did, however, pat him on the back and tell him I had missed him. I will never, ever forget what happened next. Two boys sitting behind us were giggling. Obviously, they had not shared a classroom with Stephen in first or second grade, like I had. One of them tapped Stephen on the shoulder and said, “Hey, why’d you cut all your hair off?” I was never a bully. I never picked fights in school. I rarely engaged in any kind of pushing or shoving or fighting at all. I nearly went over my seat to throttle the kid who said that, but without saying a word, Stephen stopped me with what I can only describe as the grace of being Stephen. Smiling broadly at the boy behind him, he said, “Oh, I didn’t cut it. It fell out.” It’s hard to punch a kid who has just been replied to like that. The kid said, “Oh,” and just sat back in his chair. I didn’t go after him, but I gave him a look. I turned my attention back to Stephen. “I didn’t expect you would be here, Stephen,” I said. “I didn’t think you would be able to make it.” Stephen looked straight into my soul with those incredible, defiant eyes and said, “Wild horses could not keep me from coming here tonight to get my trophy.” The rest of that event is completely lost in my memory. Nothing after that moment meant anything at all. I don’t remember going up to get my trophy. I don’t remember going home. I don’t remember Mom and Dad making a big deal about it and placing it proudly on top of the behemoth upright piano in the living room. I know all that stuff happened. It’s just that none of it mattered. Stephen left this world that summer. He died peacefully at home. Maybe facing something like a horrible disease makes kids mature faster than they would (or should) otherwise, but I can tell you this. Stephen was mature far beyond his years. Maybe that’s because Stephen had something to share with me and the other kids in Mrs. Cartmel’s class. Maybe his response to the kid behind him at the awards ceremony two years later was something that kid would need as he grew to adulthood. Maybe all of that worked together for a greater good, something no one close to Stephen could possibly understand when it happened. I was just a schoolmate, and I can’t understand it even now. Stephen was smart. Stephen was gentle. Stephen was good. The world was a better place with him in it. Maybe it’s a better place just because he passed through it. I know I am a better man for having known Stephen. I’m stronger. I’m more resilient. I look at challenges with a better attitude. I’m just better. I owe Stephen a lot. Somehow, I hope he knows that.

The history of falconry is inextricably linked with that of Frederick II as well as with his favorite son Enzio, known as Falconello or ‘the Little Falcon.’ Frederick II was an avid hunter and maintained extensive mews for his birds of prey. When on the road, his menagerie often traveled with him. In fact, some historians have argued that the emperor lost a decisive battle against the city of Parma in 1248 because at a critical moment he had gone off to hunt rather than staying with his army. According to a legend, a white gyrfalcon appeared at every major turning point in the emperor’s life, and his soul was said to have turned into a falcon upon his death. Frederick II (26 December 1194 – 13 December 1250) was known as ‘stupor mundi’ or the ‘wonder of the world’ for good reason. Born in Sicily in 1194, he spoke at least 6 languages including Arabic. He was avidly curious about the world, supported math and sciences, and commissioned translations of scientific works from Hebrew, Greek, and Arabic. In 1224, Frederick II founded the University of Naples Federico II, the world’s oldest public non-sectarian institution of higher education and research. The emperor supported the medical university of Salerno, the Scuola Medica Salernitana, remarkable for the fact that professors and students included both men and women. Frederick II was a poet in his own right and founded the Sicilian School of Poetry. He also was actively involved in the design and construction of many notable structures throughout southern Italy. One of the most famous of these is Castel del Monte in Apulia. [See https://www.malvevonhassell.com/castel-del-monte/] Frederick II, who included King of Sicily, King of Germany, King of Italy, and King of Jerusalem, as well as Holy Roman Emperor in his titles, spent over thirty years working on De Arte Venandi cum Avibus. In his prologue, he apologizes that it took him a long time to finish this work but that he had some other things to do as well, referencing “arduous and intricate governmental duties” that occupied much of his time. The Art of Falconry is an astounding compendium that draws on a variety of sources such as literature from the Middle East and the emperor’s own observations and experiments. For instance, he experimented with eggs to see if they would hatch only by the warmth of the sun, and he tried to find out if birds used their sense of smell while hunting by covering the eyes of vultures. The work addresses everything from the proper habitat for birds of prey, their capture, breeding, and training, their feeding and medical care, and even a chapter on how to release a falcon back into the wild. The entire work, highly organized and arranged like an academic tome, consists of six books that addresses the following subjects at great length and in exhaustive detail. Book I: The general habits and structure of birds Book II: Birds of prey, their capture and training Book III: The different kinds of lures and their use Book IV: Hunting cranes with the gerfalcon Book V: Hunting herons with the saker falcon Book VI: Hunting water-birds with smaller falcons Of the seven extant copies containing two books, the most famous one is a beautifully illuminated manuscript commissioned by the emperor’s son Manfred; it is housed in the Vatican Library. There are six copies with all six books. One, dating from the 13th century, is housed in the Biblioteca Universitaria in Bologna. The edition prepared by Casey Albert Wood and Florence Marjorie Fyfe includes not only an excellent translation but also various scholarly articles that provide helpful context for this astonishing compendium. Meanwhile, if you are interested in seeing the many colorful illustrations, you would be better advised to look elsewhere. The printed version of all six books spans 415 pages. Falconry was central to medieval life and culture. It had practical value in providing meat; some form of hunting with birds of prey was permitted at all levels of society. As an activity practiced by the upper classes, it also was a luxury and a status symbol. The training of falcons involves a great deal of experience and patience on part of falconers. A falconer was responsible for capturing, training, and caring for the birds. The main goal in training these wild creatures was to teach them to accept captivity and to return to it. A falconer also was responsible for making the gear used to work with falcons such as the leather hoods, jesses or leg straps, bells, lures, and leather gloves for the owners. In the Middle Ages, the position of falconer was generally handed down from father to son. An official position at medieval courts was Royal Falconer. This person ranked fourth after the king himself. In medieval times, falcons were protected. That is, anyone who disturbed a nest was punished. In Austria in the 15th century peasants could be blinded or have their property confiscated. The punishment for destruction of a falcon’s egg could be one year’s imprisonment; an individual who poached a falcon from the wild risked having his eyes poked out as a punishment. In the Middle Ages, the rules of falconry reflected the social order. Birds of prey, including the large and smaller falcons as well as hawks, were ranked in a strict hierarchy, specifying who could own what type of bird. These ranks mirrored and reinforced the social ranks in Europe in those days, with women, priests, servants, and children at the bottom of this hierarchy. King Gyr Falcon Prince Peregrine Falcon Duke Rock Falcon (subspecies of Peregrine) Earl Tiercel Peregrine Baron Bastarde Hawk Knight Saker Squire Lanner Lady Female Merlin Yeoman Goshawk or Hobby Priest Female Sparrowhawk Holy water clerk Male Sparrowhawk Knaves, servants, children Kestrel Acceptance of the social order in a clearly structured social universe was viewed as the main bulwark against chaos, while freedom was possible only within the parameters of this order. The hierarchy of humans and birds was strictly observed. Keeping a bird of prey above one’s station was punishable; it could even mean having one’s hands cut off. Falcons were treated with honor according to their rank in the hierarchy of birds. This meant ironically that they also could be punished as if they were persons of rank. Emperor Frederick had a falcon beheaded for transgressing against the social order by killing its lord. That unlucky falcon, sent after a crane, had veered off and brought down an eagle, the lord of birds. In another story, the King of Persia’s falcon also was punished after killing an eagle. Yet, the culprit was accorded the respect due to a royal bird. It was first placed upon a dais and crowned in recognition of its bravery before being beheaded. The treatise about falconry by Frederick II is both a comprehensive record of knowledge about falcons and hunting with birds of prey in the 13th century and a set of life lessons applicable to falconers as much as anyone wanting to succeed in life. The world of hunting with birds of prey served as a mirror to the accepted social order while also providing a literal training ground for individuals living in that society. The Falconer’s Apprentice is set in the intense social and political unrest of the Holy Roman Empire in the thirteenth century. The protagonist Andreas, a 15-year-old orphan and apprentice falconer, embarks on a precipitous flight across Europe to rescue the falcon Adela. Andreas, assistant to the head falconer in a castle in the north of Germany, is appalled when his young lord imposes the death sentence upon a young peregrine falcon. In deciding to hide and ultimately escape with the falcon, Andreas breaks several laws of medieval society—failing to obey a direct edict from his lord and stealing, both subject to severe punishment. I drew on excerpts from The Art of Falconry to illustrate elements of the life lessons my protagonist learns and the challenges he encounters on his journey from northern Europe to southern Italy. For instance, the discussion of what makes a good falconer, e.g., patience, hard work, and willingness to study, could apply to anyone trying to be successful. “The falconer must not be one who belittles his art and dislikes the labor involved in his calling. He must be diligent and persevering, so much so that as old age approaches he will still pursue the sport out of pure love of it. For, as the cultivation of an art is long and new methods are constantly introduced, a man should never desist in his efforts but persist in its practice while he lives so that he may bring the art itself nearer to perfection. He must possess marked sagacity; for though he may, through the teachings of experts, become familiar with all the requirements involved in the whole art of falconry, he will still have to use all his natural ingenuity in devising means of meeting emergencies.” Bad training and lack of attention have a detrimental impact on the animals in your keeping. “Falcons and other hawks are rendered clumsy or entirely unmanageable if placed under control of an ignorant interloper. By using his hearing and eyesight alone, an ignoramus may learn something about other kinds of hunting in a short time; but without an experienced teacher and frequent exercise of the art properly directed no one, noble or ignoble, can hope to gain in a short time an expert or even an ordinary knowledge of falconry.” Controlling one’s temper is of paramount importance. “A bad temper is a grave failing. A falcon may frequently commit acts that provoke the anger of her keeper, and unless he has his anger strictly under control, he may indulge in improper acts toward a sensitive bird so that she will very soon be ruined.” Frederick II offers instructions on how to travel with a falcon. “Before starting out on a long journey the bird should, for a few days, be made familiar with her hood until she either ceases her restless activities altogether or at least abandons the worst of them. She should also be handled and carried about more than if she had no journey to make.” In one of the segments, the author addresses the proper care of a bird in captivity. I found this particularly moving in light of the fact that the emperor’s favorite son, King Enzio of Sardinia, was captured by his enemies at the Battle of Fossalta in 1249. Despite repeated attempts by the emperor and others, Enzio remained imprisoned in Bologna until his death in 1272. “When a suitable location for the care of falcons has been found, an artificial nest must be built of materials like those of the wild eyrie. This place should be open on three sides (to the north, east, and west breezes) and exposed to the morning and evening sunshine.” An entire section is dedicated to how to return a falcon to the wild. My protagonist decides to release his beloved falcon Adela in the hills of Apulia. Andreas spoke to Adela as he had always done, in an easy relaxed voice. “No more traveling in a little cart for you. Today you will fly as high as you want. Maybe you will meet some brothers and sisters. You will finally get to do what you do best. You’ll see. You’ll be fierce and powerful and free.” Andreas thought of running his hand over her back and wings, but stopped at the last instant. “A falcon is not a lap dog. It is a wild animal. Never forget that!” Oswald had told him over and over again. It was time. Andreas secured the leather glove on his arm and put out his arm. She stepped onto it willingly. He slipped the hood over her head and began to walk up the narrow deer trail, careful to keep his arm steady so that she would be relaxed and calm. He quickly reached the top. The tree growth had thinned out, and he could look into the plain below and the range of hills along its edge. Andreas waited, watching the sky and the trees around him. For a moment, he thought about flying Adela and recalling her one more time. No, Adela was going to need all her energies in the next few hours. He pulled off the long jesses on her ankles so that they would not became a source of danger to her in the wild and removed the little bell attached to her left foot just above the jess. A large bird flew across the sky in the distance. Andreas lost sight of it again. Perhaps it was a falcon. He did not know how territorial other hunting birds would be. In any event, there was not much he could do about it; it would be up to Adela. If all went well, Adela would eventually find a mate. Oswald had told Andreas that falcons mate for life. A flock of small birds swept across the tree line. Andreas took the falcon’s hood off. He could sense her mounting excitement as she scanned her surroundings. He relished the firm grip of her talons on his arm. Once more, Andreas looked at the impenetrable shiny black eyes, the sharp black bars on her chest and back, and the luminous blue of her legs. Then he lifted his arm and gently launched her into the air. Adela rose swiftly, climbing higher and higher, her wing beat steady and powerful. She swooped and circled, scanning the area for prey. Something must have caught her attention beyond the tree line, because she banked sharply. Andreas followed her with his eyes as she headed toward the range of hills in the south. Then she was gone. Andreas gazed into the distance. His throat hurt. He wanted to cry, and yet he had never in his entire life been quite as exhilarated as when he watched Adela take off into the morning sky.

I wrote this little story in response to an online prompt. The prompt said that you are an adult dragon who comes upon a human toddler who has been abandoned in the forest. Write about what happens next. Here’s what spilled out of me. ========================= I really wish they would stop doing this. They’ve been doing it for years now. It’s getting old. I’m half inclined to just let this one hang there. But in the end, I know I won’t. I never do. Years ago, someone, probably a goblin, told the humans in Port Mullek that they needed to appease me with an offering from time to time, or else I would rain fire down on their town and kill them all. I suspect goblins for two reasons. First, they always try to get to the offering before I see it so they can take it for themselves. Second, I know it’s a big joke to them to spread rumors about fire breathing. Humans are afraid of us enough as it is. Add the threat of flaming breath to the equation and they feel obligated to hire foreign armies to come and wipe us out. They’ve just about done it, too. Of late, there’s been a lot less of that kind of thing because the towns are poor, and kings don’t like to lose a bunch of perfectly good soldiers fighting some dragon in a faraway land in exchange for a few bushels of grain or a couple of broken-down donkeys. Of course, I don’t have fire. It’s not something we are born with. As a matter of fact, no one knows if we can do it at all. None ever have to my knowledge. Oh sure. There are the old legends. My great-great-grandfather used to tell me stories about the mighty Krovonik, also known as the Inferno Worm, who would reduce entire towns to ashes in a single breath. I know. Hard to believe. It might be true, but my guess is it’s been highly exaggerated over the centuries. I know I’ve never seen a dragon breathe fire. I’m pretty sure great-great-grandfather never did either. It’s just something to fuel story time for the young. Back to the bag. Yes, it’s a bag, hanging from a tree branch about twenty feet off the ground, right in my line of sight. It’s wiggling, as always. It’s got some kind of cryptic writing on it, as always. The humans always paint weird symbols on the bags. I don’t know why. It’s probably part of the goblins’ stupid lies. They think they are communicating with me. They aren’t. The symbols are meaningless. Surely, they know dragons have mastered the common tongue, as well as dozens of other languages and dialects. They could just speak to me like they do one another, but they rarely try. Most of the time, they just scream and fall all over each other trying to get away from me. Their screams drown out anything I might try to say to them like, “Hey stupid. What’s wrong with you? Stop leaving little humans in bags for me. I don’t want them.” Yes, that’s what I always find in the bags. Little humans. They’re not exactly babies, but they are small. Times I have let them out of the bag, they get up and try to run away, so they’re old enough to walk. Baby humans can’t even crawl for several months. They have to be about a year or so along before they can try to walk. I guess the goblins told the humans that dragons like to eat small human children. That’s not true. Dragons won’t kill anything that can talk, unless they are being attacked or seriously threatened by the something in question. We have ethics. Mostly, we get all we need from elk, deer, and the occasional wild pig. We’ve certainly killed humans, mostly knights and other mercenaries, sent to exterminate us, but we don’t eat them. I’ve killed my share of goblins as well, but they were all asking for it, gouging at me with their nasty spears or trying to hack my legs with their crude swords. But there’s nothing a young human child could do to provoke me to kill it, and I certainly would not eat a dead one should I stumble upon it. That’s one thing the goblins must be telling the truth about when they try to get the villagers to give me their children. Dragons only eat live prey. We’re not vultures. Generally, I open the bags out of curiosity and then just wrap the kid back up and drop it off just outside the town, close enough that the villagers will find it before the goblins do and far enough away to keep the more zealous townsfolk from getting brave and charging at me with spears and axes. I don’t know what happens to the bags after I leave them. I guess the villagers assume I refused their offering for some reason. They probably think I keep the ones the goblins get to first, so that’s enough to keep them at it. So, this little bag is just hanging there, its contents wriggling and squeaking. I sigh and trudge heavily toward it, my exasperation on display for no one. I reach up and snap the branch off the tree. I’ve learned that’s safer for the occupant than ripping the bag open with a claw or trying to untie it. They don’t do well with twenty-foot falls. I put the bag down on the ground and slice the knot holding it closed with the tip of a claw. I wonder what the deal will be with this one. I say “what the deal will be” because it’s always something. Usually, it’s a birthmark, an unusual hair color, eyes that are too close together, too far apart, or an uncommon hue. I guess they’re looking for some kind of sign that would indicate the sacrifice would be worthy of my attention. Honestly, I have no idea what they are trying to do with this exercise. If only I could find out what the stupid goblins were saying to them. I hate goblins. Did I say that already? The mouth of the sack sighs open as the rope falls away. There’s more wriggling as the creature inside sees light and starts to move toward it. I wait, half annoyed and half curious. Squinting in the light and raising a limb to shield its eyes, the occupant emerges. I cannot believe what I am seeing. I’ve never seen anything like this, certainly not among humans. I can’t be certain it even is completely human, but it looks mostly like one. The face is mostly human, except for the eyes. The eyes are large and golden. The pupils are not round, but instead they are horizontal slits, kind of like my own. Yellow hair, concentrated down the center of the skull, is silky and flowing, leading to a ridge running down the entire length of the child’s back and onto its tail. Wait! Tail? Humans don’t have tails. This little one does. Again, not sure if this even is human. The skin on its face, chest, stomach, arms, and legs is mostly the soft, pinkish stuff the rest of the villagers have, but the back side of the child is covered with iridescent scales, not unlike the ones that adorn my entire body. What is this? I don’t have any time to ponder my own question. In a flash, the child assumes a determined gaze, narrowing its pupils, lowering its brow, and leaping to my left foreleg, the one I had used to open the bag. Before I can react, it’s clambered up my leg, across my shoulder, and onto the back of my head. The speed of its movements is truly impressive. I’ve got to get this thing off me. Who knows what it will do? *** I have got to stop eating those wooly mountain boars. They give me the worst nightmares. Sheesh, I feel really awful. Why is the sun so high in the sky? Have I slept that long? “Four days,” a voice answers. I spin around, shaking my stiff bones loose from their slumber. I shout out various warnings, insults, and unrepeatable slurs. I’m sure goblins have ambushed me. “I’m not a goblin,” the voice assures. Wait a minute. How does this thing, this voice, know I’m thinking about goblins? “Because I’m part of you. Don’t you understand? Actually, it’s more than that. I am you.” I am very far from understanding, and I loudly proclaim that fact to this unseen entity. I’m just about to panic, but a soothing wave of warmth flows through me. I’m actually kind of sleepy feeling. How can that be? I’ve just woken up. “Shhh,” the voice whispers. “Relax. Let me fill you in. I am you. Well, that’s sort of right. I’m part of you, but it’s that and more than that at the same time. Oh, dear. Now I’m rambling. Let me start over. There is much about our ancestry you do not know. Many thousands of years ago, our kind was much different. We ruled this world without peer and without challenge for millennia. It was a time of glory. Something happened, however. Something terrible. It’s a long story for another time but suffice it to say it interrupted our natural way of living. It changed us.” I’m feeling groggy and relaxed, but this voice is not making a lot of sense. Why is it saying, “us”? I don’t see another dragon here. There was that little creature in the bag. But that was a dream. At least, I think it was. It cannot be real. The voice snaps at me. “Pay attention!” I stop my pondering to listen. I feel like I need to ask more questions, but I am compelled by this thing, whatever it is, to just listen. “Yes, I said, ‘us.’ And yes, I know what you are thinking and why you are thinking it. Our minds are one because we are one. The ancient race existed not only of mating pairs of dragons who gave live birth, but also creatures that hatched from eggs. Yes, eggs. I know you have heard of some females laying eggs, but no one ever understood why. Actually, they just forgot why. They think it’s some kind of throwback to a time when we used to raise young from eggs, since the eggs never hatch. They just solidify into stone and are discarded. Well, most of them. Not me. “I came from one of those eggs. Your mother’s egg, to be precise. I was left in our parents’ den when they were driven out by goblin and human mercenaries. You were too young to remember, but I know you understand mother and father were lost. Our grandparents, great-grandparents, and great-great-grandparents raised you, but they didn’t give the egg a second thought. It was just a dead stone in the back of the den. An oddity not worth going back for. “Time passed. Eggs like mine wait. They wait until the other part of being matures to the point they can join it. At least, that’s the way it’s supposed to work. Almost all eggs just turn to stone and die, but not me. I awoke and hatched. I knew immediately I had to find you, but I did not know where I was. I could feel you, but you felt far away. I came out of the den, which was just a shallow cave in a hillside, and was immediately spotted and bagged by a group of humans, who were out hunting pheasants that day. They crammed me into a nasty pheasant bag and hauled me back to their village. The humans there did not know I could understand their speech, but I could. They were very excited to find me. They thought for sure I would be the sacrifice the great dragon would want. It was quickly decided they should take me out to the edge of the forest and hang me from a tree. You know the rest, but you awoke thinking it was a dream. It isn’t.” I stir from my fog and ask tentatively what this thing is exactly. I’m still pretty confused, and it’s not making a lot of sense to me what this voice is telling me. “I already told you. I am you. I am a part of you. When you let me out of the bag, I instinctively merged my body with yours. Your head probably feels a little strange. It’s larger and heavier now that I am blended into it. So, again, I am you. I am the part of you that you and every other dragon living today have been missing their whole lives. Specifically, I am your Kindling.” A thought awakens deep within me. More than a thought. A realization. A revelation. Knowledge. Joy. Completeness. Suddenly, I feel energized, free from the slumber that held me inert. I leap from the ground, spread my wings, and flap into the sky. I climb higher and higher, rolling my body and finally leveling off onto a path heading straight over the town. Faster and faster I fly, feeling the strength and power of my being, finally complete, a feeling no dragon has had for thousands of years. As I reach the edge of the village, I stall my flight, poised high in the air, giving as many townsfolk as possible a chance to notice me hovering high above their city gates. I throw my head back and open my throat in a mighty roar, enough to shake the villagers below in their boots. And now that I have their attention, I call upon my new, complete self, no longer a voice within me, but truly a part of me. I reach deep inside and summon the Kindling within. My nostrils flare and release a scarlet, blue, and golden flame that fills the sky above the town. I can only imagine the newfound terror and, hopefully, respect this display has yielded. I’m not going to hang around to find out. It’s time to put some goblins in their place.

I consider myself a pantser. That means when I start writing, I have an overall vision of what I want to achieve, but much of the planning occurs as that vision is hammered out on my computer. I feel like a sculptor, who sees promise in a misshapen slab and starts chiseling away, searching for the ideal version that exists somewhere inside. I can feel when I’m getting closer or further away, but I cannot be satisfied until I chip away all excess and hone that shape and form wanting to come to life. I’ll write something, and even as I am writing it, I feel it’s not as it should be or something is missing. Then, I see a circle. The first half is one arc of the circle, and the second half should mirror, echo, complete the first, like a bracelet latching together. Chiseling “Legend of Blackwick” Currently, I am chipping away at the slab that wants to be Legend of Blackwick. There is an ideal version of it that I am seeking as I probe closer and closer to the center. I have the first half of the circle, but I’m hopping back and forth between the second half and the first half to make sure they make a perfect fit at the end. It won’t be perfect, of course. Perfection is unattainable in this mortal sphere. But I keep reaching close as I can to that ideal version. Like a limit in calculus that can only get arbitrarily close to 0, but then springs up to infinity. WHISPERS OF CREATION: THE STORYTELLER’S CIRCLE “Whispers of Creation: The Storyteller’s Circle” captures the essence of storytelling as an evolving art form. Within this wide, landscape-oriented image, a circle gradually becomes whole, its form emerging from emptiness to fullness. Tiny words, representing ideas, themes, and the very soul of narrative, grow denser towards completion. This visual metaphor beautifully illustrates the pantser writer’s journey—how stories are sculpted from the void, each word a chisel stroke, revealing the hidden form within. It’s a tribute to the creative process, where the act of writing itself brings worlds to life, mirroring the intricate dance of imagination and expression.

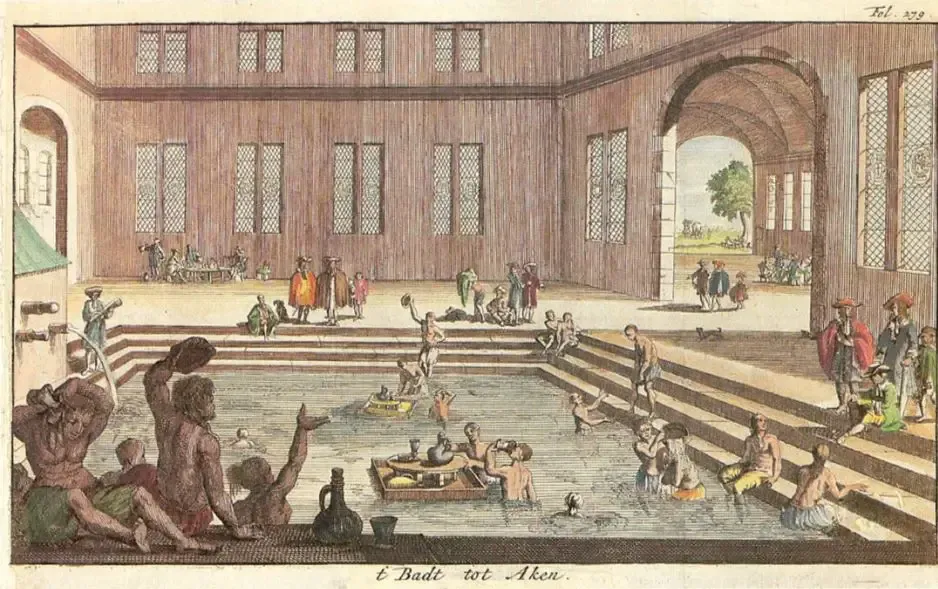

Whoever cleans himself in this bath Unites with God And cleanses in one bath His body and soul, as he should. Thomas Murner, Badenfahrt 1514 Whenever I return home from a long trip, one of my first pleasures is to take a shower, appreciative all over again of the luxury of a bathroom that is clean and bright, with a properly functioning shower head and all the comforts of 21st century living. When I sent my protagonist in my 12th century historical fiction book Alina: A Song for the Telling on her journey from Provence all the way to Jerusalem, I gave some thought to the details of traveling in the Middle Ages and the challenges of keeping clean. The Middle Ages have all too often been given a bad rap for personal hygiene and bathing options. While one certainly did not have access to private bathrooms with large smooth tubs and showers or even multiple shower heads as some more given to decadent pleasures would have it, people liked to bathe. Now some images of bathing in the Middle Ages look positively decadent. Trays set on top of large tubs hold glasses of wine and platters of food; multiple bathers sit around a chess set perched on the rim of their tub; lute players provide entertainment in the background; and servants pour pitchers of water over bathers sitting in their tubs, lined with cloth for greater comfort. Bathing was apparently a communal activity where gossip, refreshments, commercial transactions, and games could be shared while soaking in steamy water. Alina lived in a small castle in Provence. She bathed in a wooden tub with water heated over the fire. While her father had managed to run down his estate, he still had servants to help with daily tasks such as carrying heavy pitchers of water around. Filling a tub with water is hard work, and people often shared the bath water. The water undoubtedly had cooled off and was slightly murky by the time it was Alina’s turn. In Alina’s day, firewood for heating water was still readily available. Hence, most towns until the mid-1200s had public bathhouses. Of course, there was always a certain risk involved in that fires could burn out of control and consume several houses in the neighborhood. Meanwhile, thanks to overuse, forests were becoming depleted (sounds familiar, doesn’t it?), and firewood became more expensive. By the mid-1300s, bathing in hot water became a luxury that only the very wealthy could afford. While traveling, Alina’s choices were limited. When passing through towns, she could visit public baths. When staying in crowded inns, she often had to make do with a washcloth and water poured into a little bowl. Travelers and residents alike appreciated good bathing facilities as Alina finds out when encountering other travelers. Excerpt: I found it fascinating to talk to other travelers, especially those claiming to be on a pilgrimage. To my amazement, the roads were busy, and at times we had to carefully maneuver our horses around horse-drawn carts and groups of people walking along. The last family I chatted with told us they wanted to pray for their departed mother’s soul. But the husband proudly showed me a book they had purchased, called Mirabilia Urbis Romae, which apparently listed and described various sites of Rome they hoped to visit. “I heard that there are fabulous baths in Rome, and the food is said to be delicious.” His wife beamed in anticipation. “Ah, women.” Her husband smiled at her indulgently. “I am more interested in the aqueducts myself.” Perhaps we weren’t the only ones whose motives for undertaking a pilgrimage didn’t bear closer examination. Regardless of what one might think of Crusaders and their actions, there are a few areas where we have to be thankful. Not only did Crusaders help to popularize the art of knitting which originated in the Middle East, but they also introduced Europeans to soaps that might well be described as luxury items compared to the standard soap. Traditional soap was made from ash and lime mixed with oil or mutton fat and formed into solid cakes with the aid of flour. Crusaders introduced Europeans to Aleppo soap. This pleasantly scented hard soap was made with olive oil, laurel berry oil, water, and lye. Crusaders also were not averse to massages offered in steam baths or the scented oils stored in lovely glass vessels produced in the Middle East. More importantly, they liked the plumbing they encountered on their travels. Inspired by Byzantine baths as well as Roman aqueducts and sewers, they built bathing facilities in Jerusalem and Acre among other Crusader strongholds and tried to replicate some of this in Europe. When Alina and her fellow travelers reached the outskirts of Venice, they rested for several days before continuing on the road through the Byzantine Empire. Excerpt: The inn had a clean common room, and, even better, there was a public bath close by. Originally constructed by the Romans, it was a beautiful, spacious complex. Curiously, I studied the intricate mosaics on the walls of the entrance. I had never seen anything like them, so rich and vibrant, and this was merely a bath. “You like?” asked the attendant in an oddly accented Latin. I smiled at him. “Yes, I like.” “Come from Byzantium.” He pointed at the mosaics. “All new.” He handed me a towel and pointed me toward the changing rooms set aside for women. Inside I found a hot-water pool and a cold-water basin as well as an exercise area. There even was a steam room. And I had the place almost to myself. Just a few older women were soaking in the warm water. On a bench on the side of the cold-water basin, an old woman lay face down on a pillow, and an attendant massaged her back, which was exposed all the way down to her waist. Embarrassed, I looked away, and chose to make do with the hot-water pool. It was wonderful. Hours later, relaxed and content, even if my skin had shriveled from the long immersion, I returned to the inn. Later on, Alina discovers the pleasures offered by wayside inns in the Byzantine Empire: Inns in the Byzantine Empire were called caravanserais. Located along busy merchant routes all across the Empire and south to the Holy Land, these caravanserais made me think of small fortress towns. Framing a large central courtyard, they supplied everything travelers might need—sleeping areas, kitchens, blacksmith services, doctors, and even people specializing in the care of animals. The rooms were clean and comfortable, and the braziers used to provide heat seemed a lot more efficient than open hearths. “Wait till you see the marble in the bath.” “This place has a bath?” “Yes, isn’t it wonderful?” Lana laughed at me as we rode up the hill. “I have been here before. It’s because of the traders—they like their creature comforts, and pay well to have the baths set up.” Often in our daily lives, we forget how lucky we are to be able to enjoy fresh, clean water coming straight out of a tap and to be able to fill a bathtub with hot water within minutes. Crises such as the extreme water shortage in Cape Town, South Africa in 2018—narrowly averted by stringent measures and behavioral changes on part of the residents—or the disaster in Flint, Michigan (2014-2019) where lead from corroded pipes leached into the water supply of an entire city, inflicting lasting damage on many of its residents, in particular, its children, alert us to this challenge—until it fades from the media, and we forget again, oblivious to the reality that this will be one of the paramount challenges of the 21st century. In that context as well as for learning more about another age, reading about bathing and personal hygiene in the Middle Ages is enlightening and enjoyable. Occasionally, it even inspires envy.